Rebecca Valentine’s headstone in Bellefonte’s Union Cemetery (Photo by Matt Maris)

Rebecca Valentine’s headstone in Bellefonte’s Union Cemetery (Photo by Matt Maris)

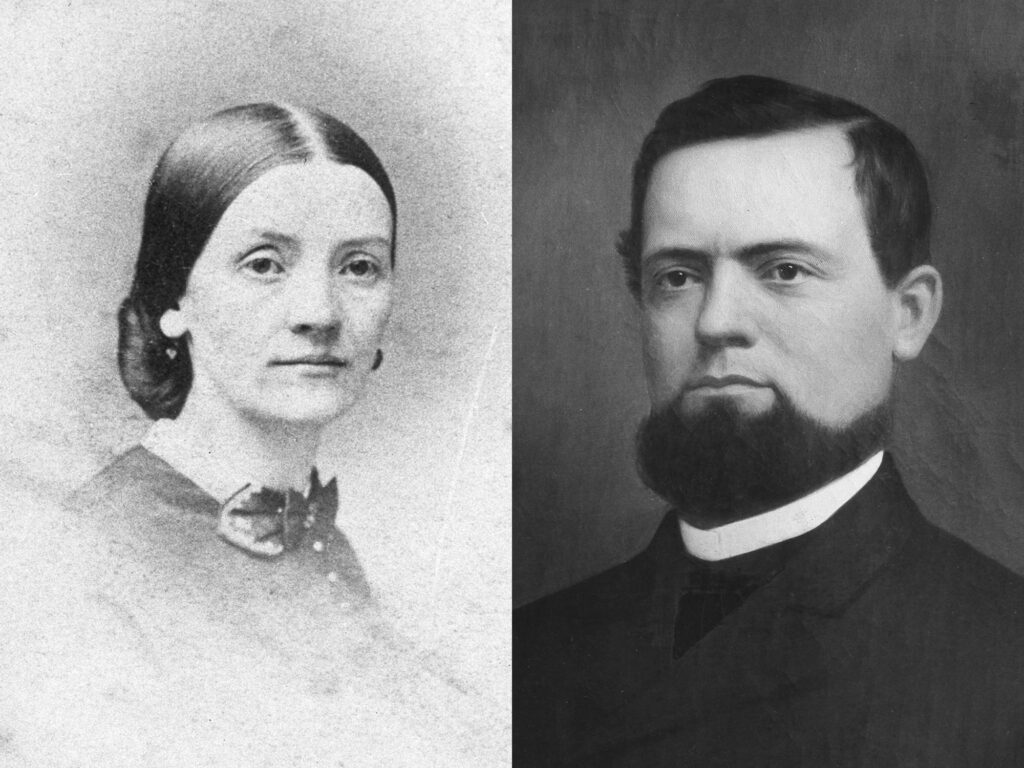

A romance blossomed in the 1860s between a world-class scientist and the daughter of an ironmaster. The first president of the Farmers’ High School, Dr. Evan Pugh, found his one and only Valentine in Bellefonte. Her name was Rebecca Valentine.

Rebecca Valentine was born on February 12, 1832, the eldest daughter of Abram S. Valentine and Clarissa Miles Valentine, a Quaker couple who hailed from Chester County. The Valentines settled in Centre County in 1815 and distinguished themselves as pioneers in the iron industry. Rebecca “lived a beautiful and useful Christian life of 89 years. In early life she was noted for a beauty of feature and brilliancy of mind that attracted men of prominence and education.”

In fact, before her courtship with Evan Pugh, a young soldier named James Beaver corresponded with her during the early scenes of the American Civil War. Beaver penned:

My dear Miss Rebecca,

I had such a sweet pleasant dream about you the last night we were a shipboard, and this delightful middle-of-june like evening reminds me so much of you and the expressive quiet of Willow Bank that I cannot refrain from writing you just a little. Not that I intend to tell you of my dream, Oh-no. Its relation would encroach too much on the romantic for my practical nature. …

While General Beaver became closely associated with Penn State much later as president and for his namesake, Beaver Stadium, it was the brilliant Dr. Evan Pugh who found his soulmate. Pugh often visited Bellefonte by carriage to discuss advances in iron production with Rebecca’s innovative father, Abram, of Valentine and Thomas Co. Dr. Pugh’s interests quickly shifted to the ironmaster’s beautiful daughter and the couple fell in love. Rebecca was the highlight of his life during a stressful time of establishing a new college during wartime.

When Pugh arrived on campus in late 1859, he immediately implemented his scientific knowledge gleaned from lectures in England, France, and Germany. He changed curriculum, introducing practical training, chemistry, geology, higher mathematics, and mineralogy to already existing courses in biology, botany, and other agricultural pursuits. Pugh taught several classes himself and oversaw “hands-on” training in farming applications, using the very limited campus funds to purchase farming equipment and livestock.

The disciplinarian also required mandatory service in which students would work on maintaining the campus, helping to erect buildings and construct roadways. Significant to Pugh’s legacy, he pushed to rename the Farmers’ High School to the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania, a move that would make it eligible for the new Morrill Land Grant funds available in 1862.

Under Pugh’s leadership, the college graduated its first class in 1861, and awarded the first agriculture degrees in the United States. Master’s degrees in scientific agriculture were offered by 1863, and the first major campus building, the “Main Building,” was completed the same year. The old farm school transitioned into a thriving scientific institution, despite stormy seas, with Pugh at the helm.

While it was Pugh who kept the college afloat, it was Rebecca who sustained him. In 1863, even after suffering injuries in a carriage accident together, Dr. Pugh slowly recovered and looked forward to their wedding. They were married at the Valentine family home, known as Willowbank, in February of 1864. Mrs. Rebecca Valentine Pugh and her husband planned to move into the new University House on campus that was being built for them, but this would never happen. Pugh never fully recovered from the accident, and he died from typhoid fever at the very home where they were wed just a few months before.

Upon Pugh’s death, his students attended his funeral as a group and delivered onto Rebecca a published resolution stating their sympathies and praise of their instructor, “kind guardian, and genial friend.” Proclaiming that their late president was “gifted with a mind of unusual vigor and clearness, enriched by ripe scholarship and varied culture, he united to these a temper so genial, so fearless and so just, and judgment so mature, as to combine a rare measure of talent of felicitous instruction with that of successful administration.”

Rebecca remained a widow for some fifty-seven years and lived in her home on West Curtin Street in Bellefonte until her death in July of 1921. She is reunited with her husband in death, and they are buried side by side in Bellefonte’s Union Cemetery, within the Valentine family plot, appropriately fenced in wrought iron. T&G

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community, and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

Sources:

Centre County Encyclopedia of History & Culture. Centre County Historical Society. centrehistory.org

“Death of Dr. Evan Pugh.” The Pittsburgh Post (Pittsburgh, PA). May 4, 1864. https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn85054562/1864-05-04/ed-1/seq-3/

Macneal, Douglas. “The Erasure of Language.” Centre County Heritage 36, no. 1 (2000): 24.

“Pugh.” Democratic Watchman (Bellefonte, PA). July 15, 1921. https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn83031981/1921-07-15/ed-1/seq-4/

Receive all the latest news and events right to your inbox.

80% of consumers turn to directories with reviews to find a local business.